by Ludger Woessmann Students from single-parent families perform significantly lower in math than students from two-parent families in virtually all countries. To a large extent, however, this achievement gap reflects differences in socioeconomic background, as measured by the number of books at home and parental education, rather than family structure alone.

When Daniel Patrick Moynihan raised the issue of family structure half a century ago, his concern was the increase in black families headed by women. Since then, the share of children raised in single-parent families in the United States has grown across racial and ethnic groups and with it evidence regarding the impact of family structure on outcomes for children. Recent studies have documented a sizable achievement gap between children who live with a single parent and their peers growing up with two parents. These patterns are cause for concern, as educational achievement is a key driver of economic prosperity for both individuals and society as a whole.

But how does the U.S. situation compare to that of other countries around the world? This essay draws on data from the 2000 and 2012 Program for International Student Assessment studies to compare the prevalence of single-parent families and how family structure relates to children’s educational achievement across countries. The 2012 data confirm that the U.S. has nearly the highest incidence of single-parent families among developed countries. And the educational achievement gap between children raised in single-parent and two-parent families, although present in virtually all countries, is particularly pronounced in the U.S.

Since 2000, there have been substantial changes in achievement gaps by family structure in many countries, with the gap widening in some countries and narrowing in others. The U.S. stands out in this analysis as a country that has seen a substantial narrowing of the educational achievement gap between children from single-parent and two-parent families. These varying trends, and the pattern for the U.S. in particular, confirm that family structure is by no means destiny. Ample evidence indicates the potential for enhancing family environments, regardless of their makeup, to improve the quality of parenting, nurturing, and stimulation, and promote healthy child development.

Evidence on Family Structure

The effect of family structure on child outcomes is a much-studied subject, and many researchers, including Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur (Growing up with a Single Parent, 1994), have explored the potentially adverse effects of single parenting on children. Single parents tend to have fewer financial resources, for example, limiting their ability to invest in their children’s development. Single parents may also have less time to spend with their children, and partnership instability may subject these parents to psychological and emotional stresses that worsen the nurturing environment for children.

Documented disadvantages of growing up in single-parent families in the United States include lower educational attainment and greater psychological distress, as well as poor adult outcomes in areas such as employment, income, and marital status. Disadvantages for children from single-parent families have also been documented in other countries, including Canada, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. But cross-country evidence has been difficult to obtain, in part because of differing methods for measuring family structure and child outcomes. The PISA studies, which asked representative samples of 15-year-olds in each participating country the same questions about their living arrangements, provide a unique opportunity to address this challenge.

At the same time, it should be noted that the descriptive patterns documented here do not necessarily capture a causal effect of living in a single-parent family. Decisions to get divorced, end cohabitation, or bear a child outside a partnership are likely related to other factors important for child development, making it difficult to separate out the influence of family structure. For example, severe stress that leads to family breakup might well have continued without the breakup and have led to worse outcomes for a child had the family remained intact. If single-parent families differ from two-parent families in unmeasured ways, then those differences may be the underlying cause of any disparities in children’s outcomes. It is even conceivable that problems a child has in school may contribute to family breakup, rather than being a consequence of it.

In addition to comparing the raw gap in educational achievement between children from single- and two-parent families, I present results that adjust for other background differences, including the number of books at home, parental education, and immigrant and language background. This type of analysis can provide useful information about the reasons educational achievement varies with family structure. It is important to keep in mind, however, that even these adjusted associations between child outcomes and family structure may well have causes other than family structure itself.

The Data

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) is an internationally standardized assessment given every three years since 2000 by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA tests the math, science, and reading achievement of representative samples of 15-year-old students in each participating country. This analysis is limited to the 28 countries that were OECD members and PISA participants in 2000.

In nearly all countries, students living in single-parent families have lower achievement on average than students living in two-parent families.

In nearly all countries, students living in single-parent families have lower achievement on average than students living in two-parent families.

PISA collects a rich array of background information in student questionnaires. Students report whether a mother (including stepmother or foster mother) usually lives at home with them, and similarly a father (including stepfather or foster father). By including students living with step- and foster parents, the group of students identified as living in two-parent families will include some students who have experienced a family separation. It is possible that, as a result, any differences between students from single- and from two-parent families will be understated in the analysis. Evidence from 2000, the one year for which it is possible to separate out students living with stepparents, suggests that this is indeed the case. In the international sample, the achievement difference would be 16 points rather than 14 points if stepparents were excluded from the two-parent families.

I limit the analysis to students who live with either one or two parents, excluding students living with neither parent and students for whom information on either the father or the mother is missing. On average across countries, 1.6 percent of students with available data from 2012 do not live with any parent (1.9 percent in the United States) and 7 percent of the total student population (11 percent in the United States) have missing data on whether a mother and/or father lives at home with them. My total 2012 sample contains more than 230,000 students or about 8,500 students per country on average. The U.S. sample consists of more than 4,300 students living in either single-parent (student lives with either mother or father only) or two-parent (student lives with both mother and father) families.

Single-Parent Families and Student Achievement

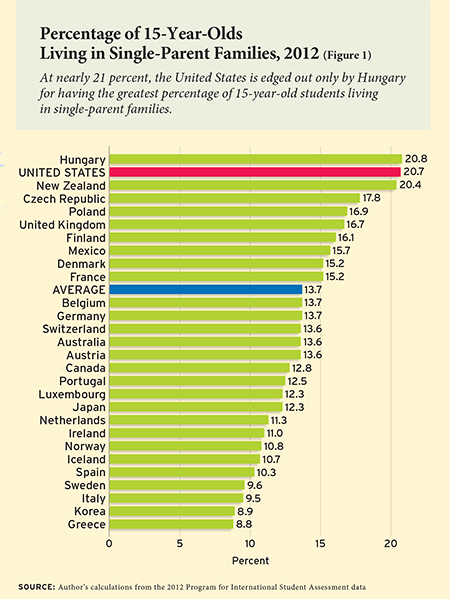

In the United States, in 2012, 21 percent of 15-year-old students lived in single-parent families (see Figure 1). Together with Hungary (also 21 percent), this puts the United States at the top among the countries. On average across all 28 countries, the share of single-parent families is 14 percent. New Zealand also has a share higher than 20 percent, while the Czech Republic has 18 percent, and Poland, the United Kingdom, Finland, Mexico, Denmark, and France have shares between 15 and 17 percent. At the other end of the spectrum, Greece, Korea, Italy, and Sweden have shares between 8.8 and 9.6 percent; Spain, Iceland, Norway, Ireland, and the Netherlands each have shares between 10 and 11.3 percent.

The vast majority of single-parent families are families with a single mother. On average across countries, 86 percent of single-parent families are headed by single mothers. In the United States, the figure is 84 percent.

To compare student achievement across countries, I focus on test scores in math, which are most readily comparable across countries. (Results for science and reading achievement in 2012, documented in the unabridged version of this study, are quite similar.) In each subject, PISA measures achievement on a scale that has a student-level standard deviation of 100 test-score points across OECD countries. That is, any achievement differences can be interpreted as percentages of a standard deviation in test scores, with one standard deviation in test-score performance representing between three and four years of learning on average. To illustrate, the average difference in math achievement between the two grade levels in our sample with the largest shares of 15-year-olds (9th and 10th grade) is 28 test-score points, which is a little more than one-quarter of a standard deviation and roughly equivalent to one year of learning or one grade level.

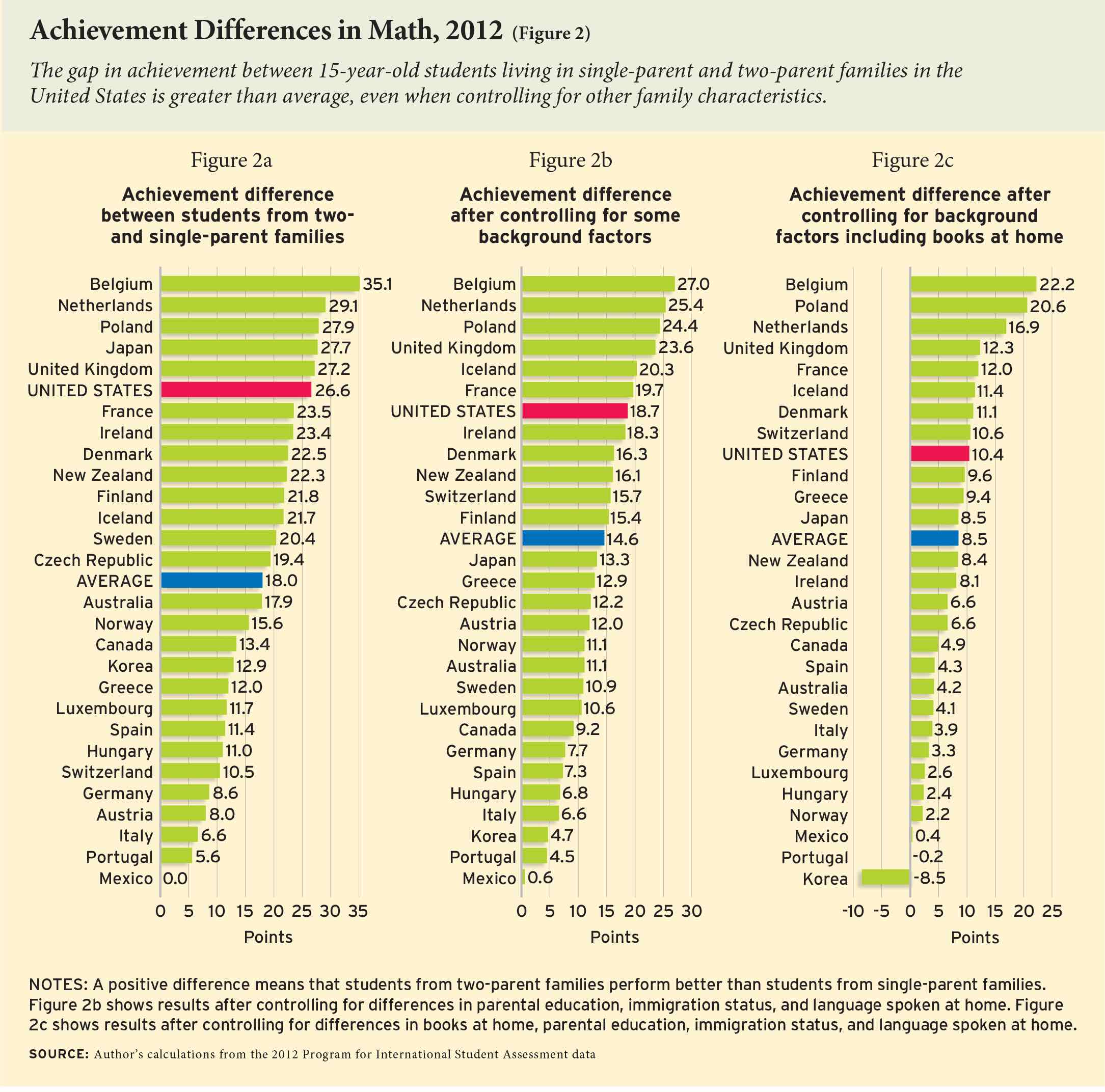

In nearly all countries, students living in single-parent families have lower achievement on average than students living in two-parent families (see Figure 2a). In the United States, the average raw achievement difference in math between students living in two-parent families and students living in single-parent families is 27 points, or roughly one grade level. The United States is one of six countries with achievement differences larger than 25 points. Belgium has the largest disparity in math achievement by family structure, at 35 points, followed by the Netherlands (29), and Poland, Japan, and the United Kingdom (27 to 28). On average across the 28 countries, students living in single-parent families score 18 points lower than students living in two-parent families.

There are exceptions, however. Mexico shows no achievement difference by family structure, and the difference is statistically insignificant in Portugal as well. The achievement difference is below 10 points in Portugal (6), Italy (7), Austria (8), and Germany (9).

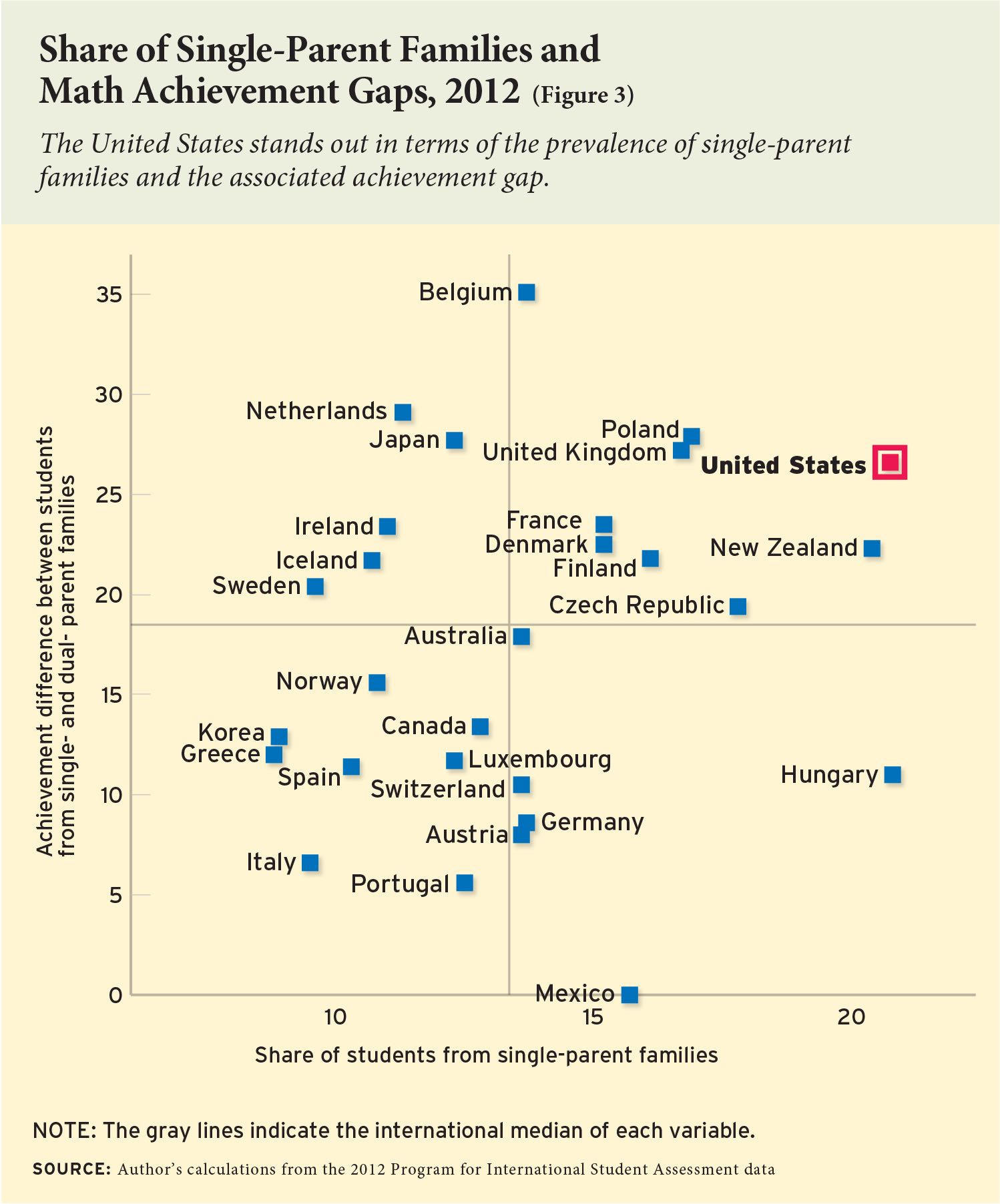

The United States stands out in this figure in terms of the prevalence of single-parent families and the associated achievement gap. Belgium and the Netherlands exhibit the highest achievement disparities, although single parenthood is not particularly prevalent in these countries. The southern European countries (Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) stand out as places with relatively low achievement disparities and relatively low prevalence of single parenthood. The German-speaking countries (Austria, Germany, and Switzerland) show similarly low achievement disparities despite their higher prevalence of single parenthood. The Asian countries (Korea and Japan) have lower levels of single-parent families but higher achievement disparities. The Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) all have similarly middling levels of achievement disparities despite varying levels of single-parenthood incidence. Finally, the eastern European countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland) have quite different achievement disparities despite the consistently high incidence of single-parent families.

The four quadrants divide the countries according to the degree of impact the prevalence of single-parent families is likely to have over the long term. For countries in the top right cell that have high values on both variables—the United States being the leading example—single parenthood may constitute a major concern for the next generation. It is quite prevalent, and the associated achievement gap is quite large. In countries in the bottom right cell, such as Hungary and Mexico, single parenthood is also quite common, but the achievement disparity is less severe. While single parenthood is less prevalent in the countries in the top left cell, such as the Netherlands and Ireland, the achievement difference is large and may still constitute a serious problem for affected students. Finally, in the bottom left cell, for countries, including Italy and Spain, where single parenthood is less prevalent and achievement disparities relatively small, there is less cause for concern.

Adjusting for Background Differences

The achievement differences reported so far are raw differences, not adjusted for background differences between students from single- and two-parent families. These raw differences may capture effects of disadvantaged backgrounds, as distinct from any independent effects of single parenthood. To provide a sense of the extent to which this might be the case, we next control for differences in family background beyond family structure.

In particular, we hold constant the number of books in the student’s home (as a proxy for socioeconomic background), the highest education level of the parent(s), immigration status (native, first-, and second-generation immigrants), and whether the national language is spoken at home. All these measures are strongly associated with student achievement, and across countries, books in the home and parental education tend to be negatively associated with single parenthood. In the cross-sectional data, though, we cannot observe whether some of these measures are preexisting characteristics of the families, in which case they represent potential biases, or whether they are an outcome of single parenthood.

Controlling for background factors has a substantial impact on the estimated achievement disparity between students living in single- and two-parent families (see Figure 2c). In the United States, the achievement disparity declines by more than 60 percent, from 27 to 10 points. On average across all countries, the disparity is reduced by half, from 18 to 9 points. While the United States still features above-average achievement differences by family structure after the adjustment, in absolute terms it differs less markedly from the international average. The countries with the largest adjusted achievement gap by family background are Belgium (22), Poland (21), and the Netherlands (17). In 12 countries, the adjusted achievement gap is below 5 points, or less than half the adjusted achievement gap in the United States. In seven countries, after the adjustment, the achievement disparity by family structure is no longer statistically significant. In Korea and Portugal, the adjusted relationship even turns negative.

With the exception of Mexico and Switzerland, where controlling for background factors hardly affects the results, the adjusted gaps are smaller in all countries than in the initial analysis. In the majority of countries (19 out of 28), the reduction in the achievement disparity between students in single- and two-parent families from controlling for observed factors is in the range of 40 to 80 percent of the raw difference in achievement.

The background factors do not contribute equally to the reduction in the achievement gap, however. In fact, controlling only for the number of books at home reduces the achievement gap by family structure across all countries to 9 points. By contrast, immigration status and language spoken at home hardly contribute to the reduction. This pattern is quite similar in the United States. That is, in the international sample, roughly half of the achievement difference between students living in single- and two-parent families simply reflects differences in socioeconomic status as captured by the number of books in the home.

With the available data, it is impossible to determine whether the relative lack of books in single-parent homes mostly reflects a preexisting feature of the families or whether it is (at least partly) an outcome of the family structure. The number of books may to some extent reflect the number of people living in the home.  Figure 2b presents achievement differences between students living in single- and two-parent families, controlling for parental education, immigration status, and language spoken at home, but not for books at home. At 19 points, this alternative adjusted achievement gap in the United States lies roughly midway between the raw difference (27) and the gap as adjusted for books at home as well as the other characteristics (10).

Figure 2b presents achievement differences between students living in single- and two-parent families, controlling for parental education, immigration status, and language spoken at home, but not for books at home. At 19 points, this alternative adjusted achievement gap in the United States lies roughly midway between the raw difference (27) and the gap as adjusted for books at home as well as the other characteristics (10).  On average across countries, the achievement gap in this model is 15 points. Thus, while controlling for books at home may well capture in part the effect of family structure, some of the overall achievement gap clearly reflects preexisting

On average across countries, the achievement gap in this model is 15 points. Thus, while controlling for books at home may well capture in part the effect of family structure, some of the overall achievement gap clearly reflects preexisting

Of course, the background factors considered here by no means capture all relevant differences in family background, although they have been found to be particularly relevant for student achievement. The adjusted achievement gaps by family structure above may partly reflect additional differences in family background rather than family structure alone.

Changes Over Time

Finally, I analyze trends in the patterns over time. To do so, I perform the same analyses as above with data from

the 2000 PISA study, when the first of these surveys was administered. (See unabridged version for details.) Over the period from 2000 to 2012, the share of 15-year-olds living in single-parent families increased from 18 to 21 percent in the United States, and from 12 to 14 percent on average in the international sample, although there are substantial differences across countries. The average achievement gap in the international sample also increased by 33 percent, from 13.6 to 18 points.

In general, countries with larger increases in the incidence of single parenthood from 2000 to 2012 tended to have larger increases in the achievement gap by family structure as well. The U.S. is a clear outlier from this pattern, however. The raw difference in math achievement between students from single- and two-parent families in the U.S. was substantially higher in 2000 than in 2012, at 37 points compared to 27 points (see Figure 4). Thus, over the course of 12 years, the achievement gap in the U.S. declined by 29 percent. In 2000, only the Netherlands, with a gap of 43 points, had a larger achievement gap than the United States. Korea (26) and Belgium (21) follow at some distance. At the other end, seven countries had achievement gaps lower than 5 points in 2000 (Iceland, Switzerland, Greece, Italy, Czech Republic, Ireland, and Mexico).

Conclusions

Single parenthood is prevalent in virtually all OECD countries, but the share of single-parent families is particularly high in the United States. Students from single-parent families perform significantly lower in math than students from two-parent families in virtually all countries. To a large extent, however, this achievement gap reflects differences in socioeconomic background, as measured by the number of books at home and parental education, rather than family structure alone. The United States belongs to the group of countries with the largest achievement gaps by family structure, although the United States was more exceptional in this regard in 2000 than in 2012. While the achievement gap between students from single- and two-parent families increased in most other OECD countries over the period, it declined in the United States.

This variation in trends shows that achievement disparities by family structure are by no means destiny. Ample evidence reveals that it is possible to enhance family environments to improve the quality of parenting, nurturing, and stimulation, and thereby promote healthy child development. Future research should investigate to what extent factors such as differing welfare systems, child support facilities, divorce regulations, and other country characteristics may lie behind the differences in achievement gaps between students from single- and two-parent families across countries and over time.

Read the original article here.

Ludger Woessmann is professor of economics at the University of Munich and director of the Ifo Center for the Economics of Education.