by Carl Jung

The spiritual problem of modern man is one of those questions which are so much a part of the age we live in that we cannot see them in the proper perspective. Modern man is an entirely new phenomenon; a modern problem is one which has just arisen and whose answer still lies in the future. In speaking of the spiritual problem of modern man we can at most frame a question, and we should perhaps frame it quite differently if we had but the faintest inkling of the answer the future will give. The question, moreover, seems rather vague; but the truth is that it has to do with something so universal that it exceeds the grasp of any single individual. We have reason enough, therefore, to approach such a problem in all modesty and with the greatest caution. This open avowal of our limitations seems to me essential, because it is these problems more than any others which tempt us to the use of high-sounding and empty words, and because I shall myself be forced to say certain things which may sound immoderate and incautious, and could easily lead us astray. Too many of us already have fallen victim to our own grandiloquence.

To begin at once with an example of such apparent lack of caution, I must say that the man we call modern, the man who is aware of the immediate present, is by no means the average man. He is rather the man who stands upon a peak, or at the very edge of the world, the abyss of the future before him, above him the heavens, and below him the whole of mankind with a history that disappears in primeval mists. The modern manor, let us say again, the man of the immediate present-is rarely met with, for he must be conscious to a superlative degree. Since to be wholly of the present means to be fully conscious of one’s existence as a man, it requires the most intensive and extensive consciousness, with a minimum of unconsciousness. It must be clearly understood that the mere fact of living in the present does not make a man modern, for in that case everyone at present alive would be so. He alone is modern who is fully conscious of the present.

The man who has attained consciousness of the present is solitary. The “modern” man has at all times been so, for every step towards fuller consciousness removes him further from his original, purely animal participation mystique with the herd, from submersion in a common unconsciousness. Every step forward means tearing oneself loose from the maternal womb of unconsciousness in which the mass of men dwells. Even in a civilized community the people who form, psychologically speaking, the lowest stratum live in a state of unconsciousness little different from that of primitives. Those of the succeeding strata live on a level of consciousness which corresponds to the beginnings of human culture, while those of the highest stratum have a consciousness that reflects the life of the last few centuries. Only the man who is modern in our meaning of the term really lives in the present; he alone has a present-day consciousness, and he alone finds that the ways of life on those earlier levels have begun to pall upon him. The values and strivings of those past worlds no longer interest him save from the historical standpoint. Thus he has become “unhistorical” in the deepest sense and has estranged himself from the mass of men who live entirely within the bounds of tradition. Indeed, he is completely modern only when he has come to the very edge of the world, leaving behind him all that has been discarded and Outgrown, and·acknowledging that he stands before the Nothing out of which All may grow.

This sounds so grand that it borders suspiciously on bathos, for nothing is easier than to affect a consciousness of the present. A great horde of worthless people do in fact give themselves a deceptive air of modernity by skipping the various stages of development and the tasks of life they represent. Suddenly they appear by the side of the truly modern man-uprooted wraiths, bloodsucking ghosts whose emptiness casts discredit upon him in his unenviable loneliness. Thus it is that the few present-day men are seen by the undiscerning eyes of the masses only through the dismal veil of those spectres, the pseudo-modems, and are confused with them. It cannot be helped; the “modern” man is questionable and suspect, and has been so at all times, beginning with Socrates and Jesus.

An honest admission of modernity means voluntarily declaring oneself bankrupt, taking the vows of poverty and chastity in a new sense, and-what is still more painful-renouncing the halo of sanctity which history bestows. To be “unhistorical” is the Promethean sin, and in this sense the modern man is sinful. A higher level of consciousness is like a burden of guilt. But, as I have said, only the man who has outgrown the stages of consciousness belonging to the past, and has amply fulfilled the duties appointed for him by his world, can achieve full consciousness of the present. To do this he must be sound and proficient in the best sense-a man who has achieved as much as other people, and even a little more. It is these qualities which enable him to gain the next highest level of consciousness.

I know that the idea of proficiency is especially repugnant to the pseudo-moderns, for it reminds them unpleasantly of their trickery. This, however, should not prevent us from taking it as our criterion of the modern man. We are even forced to do so, for unless he is proficient, the man who claims to be modern is nothing but a trickster. He must be proficient in the highest degree, for unless he can atone by creative ability for his break with tradition, he is merely disloyal to the past. To deny the past for the sake of being conscious only of the present would be sheer futility. Today has meaning only if it stands between yesterday and tomorrow. It is a process of transition that forms the link between past and future. Only the man who is conscious of the present in this sense may call himself modern.

Many people call themselves modern, especially the pseudo-moderns. Therefore the really modern man is often to be found among those who call themselves old-fashioned. They do this firstly in order to make amends for their guilty break with tradition by laying all the more emphasis on the past, and secondly in order to avoid the misfortune of being taken for pseudo-moderns. Every good quality has its bad side, and nothing good can come into the world without at once producing a corresponding evil. This painful fact renders illusory the feeling of elation that so often goes with consciousness of the present the feeling that we are the culmination of the whole history of mankind, the fulfillment and end-product of countless generations. At best it should be a proud admission of our poverty: we are also the disappointment of the hopes and expectations of the ages. Think of nearly two thousand years of Christian Idealism followed, not by the return of the Messiah and the heavenly millennium, but by the World War among Christian nations with its barbed wire and poison gas. What a catastrophe in heaven and on earth!

In the face of such a picture we may well grow humble again. It is true that modern man is a culmination, but tomorrow he will be surpassed. He is indeed the product of an age-old development, but he is at the same time the worst conceivable disappointment of the hopes of mankind. The modern man is conscious of this. He has seen how beneficent are science, technology, and organization, but also how catastrophic they can be. He has likewise seen how all well-meaning governments have so thoroughly paved the way for peace on the principle “in time of peace prepare for war” that Europe has nearly gone to rack and ruin. And as for ideals, neither the Christian Church, nor the brotherhood of man, nor international social democracy, nor the solidarity of economic interests has stood up to the acid test of reality. Today, ten years after the war,3 we observe once more the same optimism, the same organizations, the same political aspirations, the same phrases and catchwords at work. How. can we but fear that they will inevitably lead to further catastrophes? Agreements to outlaw war leave us skeptical, even while we wish them every possible success. At bottom, behind every such palliative measure there is a gnawing doubt. I believe I am not exaggerating when I say that modern man has suffered an almost fatal shock, psychologically speaking, and as a result has fallen into profound uncertainty.

These statements make it clear enough that my views are coloured by a professional bias. A doctor always spies out diseases, and I cannot cease to be a doctor. But it is essential to the physician’s art that he should not discover diseases where none exists. I will therefore not make the assertion that Western man, and the white man in particular, is sick, or that the Western world is on the verge of collapse. I am in no way competent to pass such a judgment.

Whenever you hear anyone talking about a cultural or even about a human problem, you should never forget to inquire who the speaker really is. The more general the problem, the more he will smuggle his own, most personal psychology into the account he gives of it. This can, without a doubt, lead to intolerable distortions and false conclusions which may have very serious consequences. On the other hand, the very fact that a general problem has gripped and assimilated the whole of a person is a guarantee that the speaker has really experienced it, and perhaps gained something from his sufferings. He will then reflect the problem for us in his personal life and thereby show us a truth. But if he projects his own psychology into the problem, he falsifies it by his personal bias, and on the pretense of presenting it objectively so distorts it that no truth emerges but merely a deceptive fiction.

It is of course only from my own experience with other persons and with myself that I draw my knowledge of the spiritual problem of modern man. I know something of the intimate psychic life of many hundreds of educated persons, both sick and healthy, coming from every quarter of the civilized, white world; and upon this experience I base my statements. No doubt I can draw only a one-sided picture, for everything I have observed lies in the psyche-it is all inside. I must add at once that this is a remarkable fact in itself, for the psyche is not always and everywhere to be found on the inside. There are peoples and epochs where it is found outside) because they were wholly unpsychological. As examples we may choose any of the ancient civilizations, but especially that of Egypt with its monumental objectivity and its naive confession of sins that have not been committed. We can no more feel psychic problems lurking behind the Apis tombs of Saqqara and the PyramIds than we can behind the music of Bach.

Whenever there exists some external form, be It an ideal or a ritual, by which all the yearnings and hopes of the soul are adequately expressed-as for instance in a living religion-then we may say that the psyche is outside and that there is no psychic problem, just as there is then no unconscious in our sense of the word. In consonance with this truth, the discovery of psychology falls entirely within the last decades, although long before that man was introspective and intelligent enough to recognize the facts that are the subject-matter of psychology. It was the same with technical knowledge. The Romans were familiar with all the mechanical principles and physical facts which would have enabled them to construct a steam engine, but all that came of it was the toy made by Hero of Alexandria. The reason for this is that there was no compelling necessity to go further. This need arose only with the enormous division of labour and the growth of specialization in the nineteenth century. So also a spiritual need has produced in our time the “discovery” of psychology. The psychic facts still existed earlier, of course, but they did not attract attention-no one noticed them. People got along without them. But today we can no longer get along unless we pay attention to the psyche.

It was men of the medical profession who were the first to learn this truth. For the priest, the psyche can only be something that needs fitting into a recognized form or system of belief in order to ensure its undisturbed functioning. So long as this system gives true expression to life, psychology can be nothing but a technical adjuvant to healthy living, and the psyche cannot be regarded as a factor sui generis. While man still lives as a herd-animal he has no psyche of his own, nor does he need any, except the usual belief in the immortality of the soul. But as soon as he has outgrown whatever local form of religion he was born to-as soon as this religion can no longer embrace his life in all its fullness-then the psyche becomes a factor in its own right which cannot be dealt with by the customary measures. It is for this reason that we today have a psychology founded on experience, and not upon articles of faith or the postulates of any philosophical system. The very fact that We have such a psychology is to me symptomatic of a profound convulsion of the collective psyche. For the collective psyche shows the same pattern of change as the psyche of the individual. So long as all goes well and all our psychic energies find an outlet in adequate and well-regulated ways, we are disturbed by nothing from within. No uncertainty or doubt besets us, and we cannot be divided against ourselves. But no sooner are one or two channels of psychic activity blocked up than phenomena of obstruction appear. The stream tries to flow back against the current, the inner man wants something different from the outer man, and we are at war with ourselves. Only then, in this situation of distress, do we discover the psyche as something which thwarts our will, which is strange and even hostile to us, and which is incompatible with our conscious standpoint. Freud’s psychoanalytic endeavours show this process in the clearest way. The very first thing he discovered was the existence of sexually perverse and criminal fantasies which at their face value are wholly incompatible with the conscious outlook of civilized man. A person who adopted the standpoint of these fantasies would be nothing less than a rebel, a criminal, or a madman.

We cannot suppose that the unconscious or hinterland of man’s mind has developed this aspect only in recent times. Probably it was always there, in every culture. And although every culture had its destructive opponent, a Herostratus who burned down its temples, no culture before ours was ever forced to take these psychic undercurrents in deadly earnest. The psyche was merely part of a metaphysical system of some sort. But the conscious, modern man can no longer refrain from acknowledging the might of the psyche, despite the most strenuous and dogged efforts at self-defence. This distinguishes our time from all others. We can no longer deny that the dark stirrings of the unconscious are active powers, that psychic forces exist which, for the present at least, cannot be fitted into our rational world order. We have even elevated them into a science-one more proof of how seriously we take them. Previous centuries could throw them aside unnoticed; for us they are a shirt of Nessus which we cannot strip off.

The revolution in our conscious outlook, brought about by the catastrophic results of the World War, shows itself in our inner life by the shattering of our faith in ourselves and our own worth. We used to regard foreigners as political and moral reprobates, but the modern man is forced to recognize that he is politically and morally just like anyone else. Whereas formerly I believed it was my bounden duty to call others to order, I must now admit that I need calling to order myself, and that I would do better to set my own house to rights first. I admit this the more readily because I realize only too well that my faith in the rational organization of the world-that old dream of the millennium when peace and harmony reign-has grown pale. Modern man’s skepticism in this respect has chilled his enthusiasm for politics and world-reform; more than that, it is the worst possible basis for a smooth flow of psychic energies into the outer world, just as doubt concerning the morality of a friend is bound to prejudice the relationship and hamper its development. Through his skepticism modern man is thrown back on himself; his energies flow towards their source, and the collision washes to the surface those psychic contents which are at all times there, but lie hidden in the silt so long as the stream flows smoothly in its course. How totally different did the world appear to medieval man! For him the earth was eternally fixed and at rest in the centre of the universe, circled by a sun that solicitously bestowed its warmth. Men were all children of God under the loving care of the Most High, who prepared them for eternal blessedness; and all knew exactly what they should do and how they should conduct themselves in order to rise from a corruptible world to an incorruptible and joyous existence. Such a life no longer seems real to us, even in our dreams. Science has long ago torn this lovely veil to shreds. That age lies as far behind as childhood, when one’s own father was unquestionably the handsomest and strongest man on earth.

Modern man has lost all the metaphysical certainties of his medieval brother, and set up in their place the ideals of material security, general welfare and humanitarianism. But anyone who has still managed to preserve these ideals unshaken must have been injected with a more than ordinary dose of optimism. Even security has gone by the board, for modern man has begun to see that every step forward in material “progress” steadily increases the threat of a still more stupendous catastrophe. The imagination shrinks in terror from such a picture. What are we to think when the great cities today are perfecting defense measures against gas attacks, and even practice them in dress rehearsals? It can only mean that these attacks have already been planned and provided for, again on the principle “in time of peace prepare for war.” Let man but accumulate sufficient engines of destruction and the devil within him will soon be unable to resist putting them to their fated use. It is well known that fire-arms go off of themselves if only enough of them are together.

An intimation of the terrible law that governs blind contingency, which Heraclitus called the rule of enantiodromia (a running towards the opposite), now steals upon modern man through the by-ways of his mind, chilling him with fear and paralyzing his faith in the lasting effectiveness of social and political measures in the face of these monstrous forces. If he turns away from the terrifying prospect of a blind world in which building and destroying successively tip the scales, and then gazes into the recesses of his own mind, he will discover a chaos and a darkness there which everyone would gladly ignore. Science has destroyed even this last refuge; what was once a sheltering haven has become a cesspool.

And yet it is almost a relief to come upon so much evil in the depths of our own psyche. Here at least, we think, is the root of all the evil in mankind. Even though we are shocked and disillusioned at first, we still feel, just because these things are part of our psyche, that we have them more or less in hand and can correct them or at any rate effectively suppress them. We like to assume that, if we succeeded in this, we should at least have rooted out some fraction of the evil in the world. Given a widespread knowledge of the unconscious, everyone could see when a statesman was being led astray by his own bad motives. The very newspapers would pull him up: “Please have yourself analyzed; you are suffering from a repressed father-complex.”

I have purposely chosen this grotesque example to show to what absurdities we are led by the illusion that because something is psychic it is under our control. It is, however, true that much of the evil in the world comes from the fact that man in general is hopelessly unconscious, as it is also true that with increasing insight we can combat this evil at its source in ourselves, in the same way that science enables us to deal effectively with injuries inflicted from without.

The rapid and worldwide growth of a psychological interest over the last two decades shows unmistakably that modern man is turning his attention from outward material things to his own inner processes. Expressionism in art prophetically anticipated this subjective development, for all art intuitively apprehends coming changes in the collective unconsciousness.

The psychological interest of the present time is an indication that modem man expects something from the psyche which the outer world has not given him: doubtless something which our religion ought to contain, but no longer does contain, at least for modern man. For him the various forms of religion no longer appear to come from within, from the psyche; they seem more like items from the inventory of the outside world. No spirit not of this world vouchsafes him inner revelation; instead, he tries on a variety of religions and beliefs as if they were Sunday attire, only to lay them aside again like worn-out clothes.

Yet he is somehow fascinated by the almost pathological manifestations from the hinterland of the psyche, difficult though it is to explain how something which all previous ages have rejected should suddenly become interesting. That there is a general interest in these matters cannot be denied, however much it offends against good taste. I am not thinking merely of the interest taken in psychology as a science, or of the still narrower interest in the psychoanalysis of Freud, but of the widespread and ever-growing interest in all sorts of psychic phenomena, including spiritualism, astrology, Theosophy, parapsychology, and so forth. The world has seen nothing like it since the end of the seventeenth century. We can compare it only to the flowering of Gnostic thought in the first and second centuries after Christ. The spiritual currents of our time have, in fact, a. deep affinity.with Gnosticism. There is even an “Eglise gnostique de la France,” and I know of two schools in Germany which openly declare themselves Gnostic. The most impressive movement numerically is undoubtedly Theosophy, together with its continental sister, Anthroposophy; these are pure Gnosticism in Hindu dress. Compared with them the interest in scientific psychology is negligible. What is striking about these Gnostic systems is that they are based exclusively on the manifestations of the unconscious, and that their moral teachings penetrate into the dark side of life, as is clearly shown by the refurbished European version of Kundalini-yoga. The same is true of parapsychology, as everyone acquainted with this subject will agree.

The passionate interest in these movements undoubtedly arises from psychic energy which can no longer be invested in obsolete religious forms. For this reason such movements have a genuinely religious character, even when they pretend to be scientific. It changes nothing when Rudolf Steiner calls his Anthroposophy “spiritual science,” or when Mrs. Eddy invents a “Christian Science.” These attempts at concealment merely show that religion has grown suspect-almost as suspect as politics and world-reform.

I do not believe that I am going too far when I say that modern man, in contrast to his nineteenth-century brother, turns to the psyche with very great expectations, and does so without reference to any traditional creed but rather with a view to Gnostic experience. The fact that all the movements I have mentioned give themselves a scientific veneer is not just a grotesque caricature or a masquerade, but a positive sign that they are actually pursuing “science,” i.e., knowledge instead of faith which is the essence of the Western forms of religion. Modern man abhors faith and the religions based upon it. He holds them valid only so far as their knowledge-content seems to accord with his own experience of the psychic background. He wants to know-to experience for himself.

The age of discovery has only just come to an end in our day, when no part of the earth remains unexplored; it began when men would no longer believe that the Hyperboreans were one-footed monsters, or something of that kind, but wanted to find out and see with their own eyes what existed beyond the boundaries of the known world. Our age is apparently setting out to discover what exists in the psyche beyond consciousness. The question asked in every spiritualistic circle is: What happens after the medium has lost consciousness? Every Theosophist asks: What shall I experience at the higher levels of consciousness? The question which every astrologer asks is: What are the operative forces that determine my fate despite my conscious intention? And every psychoanalyst wants to know: What are the unconscious drives behind the neurosis?

Our age wants to experience the psyche for itself. It wants original experience and not assumptions, though it is willing to make use of all the existing assumptions as a means to this end, including those of the recognized religions and the authentic sciences. The European of yesterday will feel a slight shudder run down his spine when he gazes more deeply into these delvings. Not only does he consider the subject of this so-called research obscure and shuddersome, but even the methods employed seem to him a shocking misuse of man’s finest intellectual attainments. What is the professional astronomer to say when he is told that at least a thousand times more horoscopes are cast today than were cast three hundred years ago? What will the educator and advocate of philosophical enlightenment say about the fact that the world has not grown poorer by a single superstition since the days of antiquity? Freud himself, the founder of psychoanalysis, has taken the greatest pains to throw as glaring a light as possible on the dirt and darkness and evil of the psychic background, and to interpret it in such a way as to make us lose all desire to look for anything behind it except refuse and smut. He did not succeed, and his attempt at deterrence has even brought about the exact opposite-an admiration for all this filth. Such a perverse phenomenon would normally be inexplicable were it not that even the scatologists are drawn by the secret fascination of the psyche.

There can be no doubt that from the beginning of the nineteenth century-ever since the time of the French Revolution the psyche has moved more and more into the foreground of man’s interest, and with a steadily increasing power of attraction. The enthronement of the Goddess of Reason in Notre Dame seems to have been a symbolic gesture of great significance for the Western world-rather like the hewing down of Wotan’s oak by Christian missionaries. On both occasions no avenging bolt from heaven struck the blasphemer down.

It is certainly more than an amusing freak of history that just at the time of the Revolution a Frenchman, Anquetil du Perron, should be living in India and, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, brought back with him a translation of the Oupnek’hat) a collection of fifty Upanishads, which gave the West its first deep insight into the baffling mind of the East. To the historian this is a mere coincidence independent of the historical nexus of cause and effect. My medical bias prevents me from seeing it simply as an accident. Everything happened in accordance with a psychological law which is unfailingly valid in personal affairs. If anything of importance is devalued in our conscious life, and perishes-so runs the law-there arises a compensation in the unconscious. We may see in this an analogy to the conservation of energy in the physical world, for our psychic processes also have a quantitative, energic aspect. No psychic value can disappear without being replaced by another of equivalent intensity. This is a fundamental rule which is repeatedly verified in the daily practice of the psychotherapist and never fails. The doctor in me refuses point blank to consider the life of a people as something that does not conform to psychological law. For him the psyche of a people is only a somewhat more complex structure than the psyche of an individual. Moreover, has not a poet spoken of the “nations of his soul”? And quite correctly, it seems to me, for in one of its aspects the psyche is not individual, but is derived from the nation, from the collectivity, from humanity even. In some way or other we are part of a single, all-embracing psyche, a single “greatest man,” the homo maximus, to quote Swedenborg.

And so we can draw a parallel: just as in me, a single individual, the darkness calls forth a helpful light, so it does in the psychic life of a people. In the crowds that poured into Notre Dame, bent on destruction, dark and nameless forces were at work that swept the individual off his feet; these forces worked also upon Anquetil du Perron and provoked an answer which has come down in history and speaks to us through the mouths of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche. For he brought the Eastern mind to the West, and its influence upon us we cannot as yet measure. Let us beware of underestimating it! So far, indeed, there is little of it to be seen on the intellectual surface: a handful of orientalists, one or two Buddhist enthusiasts, a few sombre celebrities like Madame Blavatsky and Annie Besant with her Krishnamurti. These manifestations are like tiny scattered islands in the ocean of mankind; in reality they are the peaks of submarine mountain-ranges. The cultural Philistines believed until recently that astrology had been disposed of long since and was something that could safely be laughed at. But today, rising out of the social deeps, it knocks at the doors of the universities from which it was banished some three hundred years ago. The same is true of Eastern ideas; they take root in the lower levels and slowly grow to the surface. Where did the five or six million Swiss francs for the Anthroposophist temple at Dornach come from? Certainly not from one individual. Unfortunately there are no statistics to tell us the exact number of avowed Theosophists today, not to mention the unavowed. But we can be sure there are several millions of them. To this number we must add a few million Spiritualists of Christian or Theosophist leanings.

Great innovations never come from above; they come invariably from below, just as trees never grow from the sky downward, but upward from the earth. The upheaval of our world and the upheaval of our consciousness are one and the same. Everything has become relative and therefore doubtful. And while man, hesitant and questioning, contemplates a world that is distracted with treaties of peace and pacts of friendship, with democracy and dictatorship, capitalism and Bolshevism, his spirit yearns for an answer that will allay the turmoil of doubt and uncertainty. And it is just the people from the obscurer levels who follow the unconscious drive of the psyche; it is the much-derided, silent folk of the land, who are less infected with academic prejudices than the shining celebrities are wont to be. Looked at from above, they often present a dreary or laughable spectacle; yet they are as impressively simple as those Galileans who were once called blessed. Is it not touching to see the offscourings of man’s psyche gathered together in compendia a foot thick? We find the merest babblings, the most absurd actions, the wildest fantasies recorded with scrupulous care in the volumes of Anthropophyteia) while men like Havelock Ellis and Freud have dealt with like matters in serious treatises which have been accorded all scientific honours. Their reading public is scattered over the breadth of the civilized, white world. How are we to explain this zeal, this almost fanatical worship of everything unsavoury? It is because these things are psychological-they are of the substance of the psyche and therefore as precious as fragments of manuscript salvaged from ancient middens. Even the secret and noisome things of the psyche are valuable to modern man because they serve his purpose. But what purpose?

Freud prefixed to his Interpretation of Dreams the motto: Flectere si nequeo superos Acheronta movebo-“lf I cannot bend the gods on high, I will at least set Acheron in uproar.” But to what purpose?

The gods whom we are called upon to dethrone are the idolized values of our conscious world. Nothing, as we know, discredited the ancient gods so much as their love-scandals, and now history is repeating itself. People are laying bare the dubious foundations of our belauded virtues and incomparable ideals, and are calling out to us in triumph: “There are your man-made gods, mere snares and delusions tainted with human baseness-whited sepulchres full of dead men’s bones and of all uncleanness.” We recognize a familiar strain, and the Gospel words which we failed to digest at Confirmation come to life again.

I am deeply convinced that these are not just vague analogies. There are too many persons to whom Freudian psychology is dearer than the Gospels, and to whom Bolshevism means more than civic virtue. And yet they are all our brothers, and in each of us there is at least one voice which seconds them, for in the end there is one psyche which embraces us all.

The unexpected result of this development is that an uglier face is put upon the world. It becomes so ugly that no one can love it any longer; we cannot even love ourselves, and in the end there is nothing in the outer world to draw us away from the reality of the life within. Here, no doubt, we have the true significance of this whole development. After all, what does Theosophy, with its doctrines of karma and reincarnation, seek to teach except that this world of appearance is but a temporary health-resort for the morally unperfected? It depreciates the intrinsic value of the present-day world no less radically than does the modern outlook, but with the help of a different technique; it does not vilify our world, but grants it only a relative meaning in that it promises other and higher worlds. The result in either case is the same.

I admit that all these ideas are extremely unacademic, the truth being that they touch modern man on the side where he is least conscious. Is it again a mere coincidence that modern thought has had to come to terms with Einstein’s relativity theory and with nuclear theories which lead us away from determinism and border on the inconceivable? Even physics is volatilizing our material world. It is no wonder, then, in my opinion, if modern man falls back on the reality of psychic life and expects from it that certainty which the world denies him.

Spiritually the Western world is in a precarious situation, and the danger is greater the more we blind ourselves to the merciless truth with illusions about our beauty of soul. Western man lives in a thick cloud of incense which he burns to himself so that his own countenance may be veiled from him in the smoke. But howdo we strike men of another colour? What do China and India think of us? What feelings do we arouse in the black man? And what about all those whom we rob of their lands and exterminate with rum and venereal disease?

I have an American Indian friend who is a Pueblo chieftain. Once when we were talking confidentially about the white man, he said to me: “We don’t understand the whites. They are always wanting something, always restless, always looking for something. What is it? We don’t know. ‘Ve can’t understand them. They have such sharp noses, such thin, cruel lips, such lines in their faces. We think they are all crazy.”

My friend had recognized, without being able to name it, the Aryan bird of prey with his insatiable lust to lord it in every land, even those that concern him not at all. And he had also noted that megalomania of ours which leads us to suppose, among other things, that Christianity is the only truth and the White Christ the only redeemer. After setting the whole East in turmoil with our science and technology, and exacting tribute from it, we send our missionaries even to China. The comedy of Christianity in Africa is really pitiful. There the stamping 0.ut of polygamy, no doubt highly pleasing to God, has given rise to prostitution on such a scale that in Uganda alone twenty thousand pounds are spent annually on preventives of venereal Infection: And the good European pays his missionaries for these edifying achievements! Need we also mention the story of suffering in Polynesia and the blessings of the opium trade?

That is how the European looks when he is extricated from the cloud of his own moral incense. No wonder that unearthing the psyche is like undertaking a full-scale drainage operation. Only a great idealist like Freud could devote a lifetime to such unclean work. It was not he who caused the bad smell, but all of us-we who think ourselves so clean and decent from sheer ignorance and the grossest self-deception. Thus our psychology, the acquaintance with our own souls, begins in every respect from the most repulsive end, that is to say with all those things which we do not wish to see.

But if the psyche consisted only of evil and worthless things, no power on earth could induce the normal man to find it attractive. That is why people who see in Theosophy nothing but lamentable intellectual superficiality, and in Freudian psychology nothing but sensationalism, prophesy an early and inglorious end to these movements. They overlook the fact that such movements derive their force from the fascination of the psyche, and that it will express itself in these forms until they are replaced by something better. They are transitional or embryonic stages from which new and riper forms will emerge.

We have not yet realized that Western Theosophy is an amateurish, indeed barbarous imitation of the East. We are just beginning to take up astrology again, which to the Oriental is his daily bread. Our studies of sexual life, originating in Vienna and England, are matched or surpassed by Hindu teachings on this subject. Oriental texts ten centuries old introduce us to philosophical relativism, while the idea of indeterminacy, newly broached in the West, is the very basis of Chinese science. As to our discoveries in psychology, Richard Wilhelm has shown me that certain complicated psychic processes are recognizably described in ancient Chinese texts. Psychoanalysis itself and the lines of thought to which it gives rise-a development which we consider specifically Western-are only a beginner’s attempt compared with what is an immemorial art in the East. It may not perhaps be known that parallels between psychoanalysis and yoga have already been drawn by Oscar Schmitz.

Another thing we have not realized is that while we are turning the material world of the East upside down with our technical proficiency, the East with its superior psychic proficiency is throwing our spiritual world into confusion. We have never yet hit upon the thought that while we are overpowering the Orient from without, it may be fastening its hold on us from within. Such an idea strikes us as almost insane, because we have eyes only for obvious causal connections and fail to see that we must lay the blame for the confusion of our intellectual middle class at the doors of Max Muller, Oldenberg, Deussen, Wilhelm, and others like them. What does the example of the Roman Empire teach us? After the conquest of Asia Minor, Rome became Asiatic; Europe was infected by Asia and remains so today. Out of Cilicia came the Mithraic cult, the religion of the Roman legions, and it spread from Egypt to fog-bound Britain. Need I point out the Asiatic origin of Christianity?

The Theosophists have an amusing idea that certain Mahatmas, seated somewhere in the Himalayas or Tibet, inspire and direct every mind in the world. So strong, in fact, can be the influence of the Eastern belief in magic that Europeans of sound mind have assured me that every good thing I say is unwittingly inspired in me by the Mahatmas, my own inspirations being of no account whatever. This myth of the Mahatmas, widely circulated in the West and firmly believed, far from being nonsense, is-like every myth-an important psychological truth. It seems to be quite true that the East is at the bottom of the spiritual change we are passing through today. Only, this East is not a Tibetan monastery full of Mahatmas, but lies essentially within us. It is our own psyche, constantly at work creating new spiritual forms and spiritual forces which may help us to subdue the boundless lust for prey of Aryan man. We shall perhaps come to know something of that narrowing of horizons which has grown in the East into a dubious quietism, and also something of that stability which human existence acquires when the claims of the spirit become as imperative as the necessities of social life. Yet in this age of Americanization we are still far from anything of the sort; it seems to me that w~ are only at the threshold of a new spiritual epoch. I do not wish to pass myself off as a prophet, but one can hardly attempt to sketch the spiritual problem of modern man without mentioning the longing for rest in a period of unrest, the longing for security in an age of insecurity. It is from need and distress that new forms of existence arise, and not from idealistic requirements or mere wishes.

To me the crux of the spiritual problem today is to be found in the fascination which the psyche holds for modern man. If we are pessimists, we shall call it a sign of decadence; if we are optimistically inclined, we shall see in it the promise of a far-reaching spiritual change in the Western world. At all events, it is a significant phenomenon. It is the more noteworthy because it is rooted in the deeper social strata, and the more important because it touches those irrational and-as history shows -incalculable psychic forces which transform the life of peoples and civilizations in ways that are unforeseen and unforeseeable. These are the forces, still invisible to many persons today, which are at the bottom of the present “psychological” interest. The fascination of the psyche is not by any means a morbid perversity; it is an attraction so strong that it does not shrink even from what it finds repellent.

Along the great highways of the world everything seems desolate and outworn. Instinctively modern man leaves the trodden paths to explore the by-ways and lanes, just as the man of the Greco-Roman world cast off his defunct Olympian gods and turned to the mystery cults of Asia. Our instinct turns outward, and appropriates Eastern theosophy and magic; but it also turns inward, and leads us to contemplate the dark background of the psyche. It does this with the same skepticism and the same ruthlessness which impelled the Buddha to sweep aside his two million gods that he might attain the original experience which alone is convincing.

And now we must ask a final question. Is what I have said of modern man really true, or is it perhaps an illusion? There can be no doubt whatever that to many millions of Westerners the facts I have adduced are wholly irrelevant and fortuitous, and regrettable aberrations to a large number of educated persons. But-did a cultivated Roman think any differently when he saw Christianity spreading among the lower classes? Today the God of the West is still a living person for vast numbers of people, just as Allah is beyond the Mediterranean, and the one believer holds the other an inferior heretic, to be pitied and tolerated failing all else. To make matters worse, the enlightened European is of the opinion that religion and such things are good enough for the masses and for women, but of little consequence compared with immediate economic and political questions.

So I am refuted all along the line, like a man who predicts a thunderstorm when there is not a cloud in the sky. Perhaps it is a storm below the horizon, and perhaps it will never reach us. But what is significant in psychic life always lies below the horizon of consciousness, and when we speak of the spiritual problem of modern man we are speaking of things that are barely visible-of the most intimate and fragile things, of flowers that open only in the night. In daylight everything is clear and tangible, but the night lasts as long as the day, and we live in the night-time also. There are people who have bad dreams which even spoil their days for them. And for many people the day’s life is such a bad dream that they long for the night when the spirit awakes. I believe that there are nowadays a great many such people, and this is why I also maintain that the spiritual problem of modern man is much as I have presented it.

I must plead guilty, however, to the charge of one-sidedness, for I have passed over in silence the spirit of the times, about which everyone has so much to say because it is so clearly apparent to us all. It shows itself in the ideal of internationalism and supernationalism, embodied in the League of Nations and the like; we see it also in sport and, significantly, in cinema and jazz. These are characteristic symptoms of our time, which has extended the humanistic ideal even to the body. Sport puts an exceptional valuation on the body, and this tendency is emphasized still further in modern dancing. The cinema, like the detective story, enables us to experience without danger to ourselves all the excitements, passions, and fantasies which have to be repressed in a humanistic age. It is not difficult to see how these symptoms link up with our psychological situation. The fascination of the psyche brings about a new self-appraisal, a reassessment of our fundamental human nature. “\le can hardly be surprised if this leads to a rediscovery of the body after its long subjection to the spirit-we are even tempted to say that t?e flesh is getting its own back. When Keyserling sarcastically singles out the chauffeur as the culture-hero of our time, he has struck, as he often does, close to the mark. The body lays claim to equal recognition; it exerts the same fascination as the psyche. If we are still caught in the old idea of an antithesis between mind and matter, this state of affairs must seem like an unbearable contradiction. But if we can reconcile ourselves to the mysterious truth that the spirit is the life of the body seen from within, and the body the outward manifestation of the life of the spirit-the two being really one-then we can understand why the striving to transcend the present level of consciousness through acceptance of the unconscious must give the body its due, and why recognition of the body cannot tolerate a philosophy that denies it in the name of the spirit. These claims of physical and psychic life, incomparably stronger than they were in the past, may seem a sign of decadence, but they may also signify a rejuvenation, for as Holderlin says:

Where danger is,

Arises salvation also.

And indeed we see, as the Western world strikes up a more rapid tempo-the American tempo-the exact opposite of quietism and world-negating resignation. An unprecedented tension arises between outside and inside, between objective and subjective reality. Perhaps it is a final race between aging Europe and young America; perhaps it is a healthier or a last desperate effort to escape the dark sway of natural law, and to wrest a yet greater and more heroic victory of waking consciousness over the sleep of the nations. This is a question only history can answer.

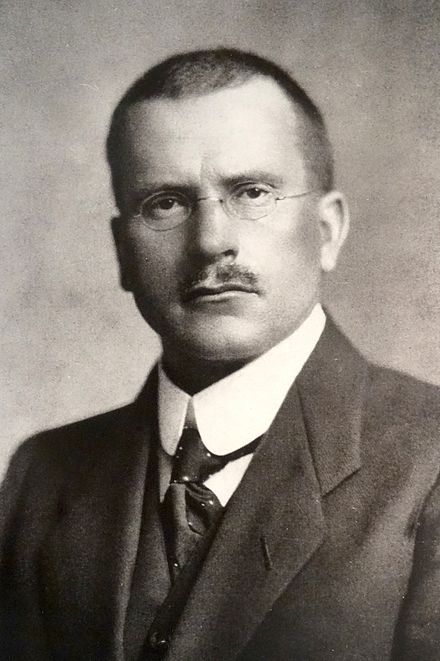

Author: Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung (26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung’s work was influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philosophy, and religious studies. Jung worked as a research scientist at the famous Burghölzli hospital, under Eugen Bleuler. During this time, he came to the attention of Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. The two men conducted a lengthy correspondence and collaborated, for a while, on a joint vision of human psychology.